Clearing the Path

Whether a trail is one mile or 1,000 miles, in a city or in the middle of a forest, someone has to take care of it. Someone has to clear the fallen trees after a storm or put in a water bar to mitigate erosion so you and I can get outside. BRO hit the road with two maintenance crews to get a feel for all the work that goes into keeping trails open to the public.

James River Park System (Richmond, Va.)

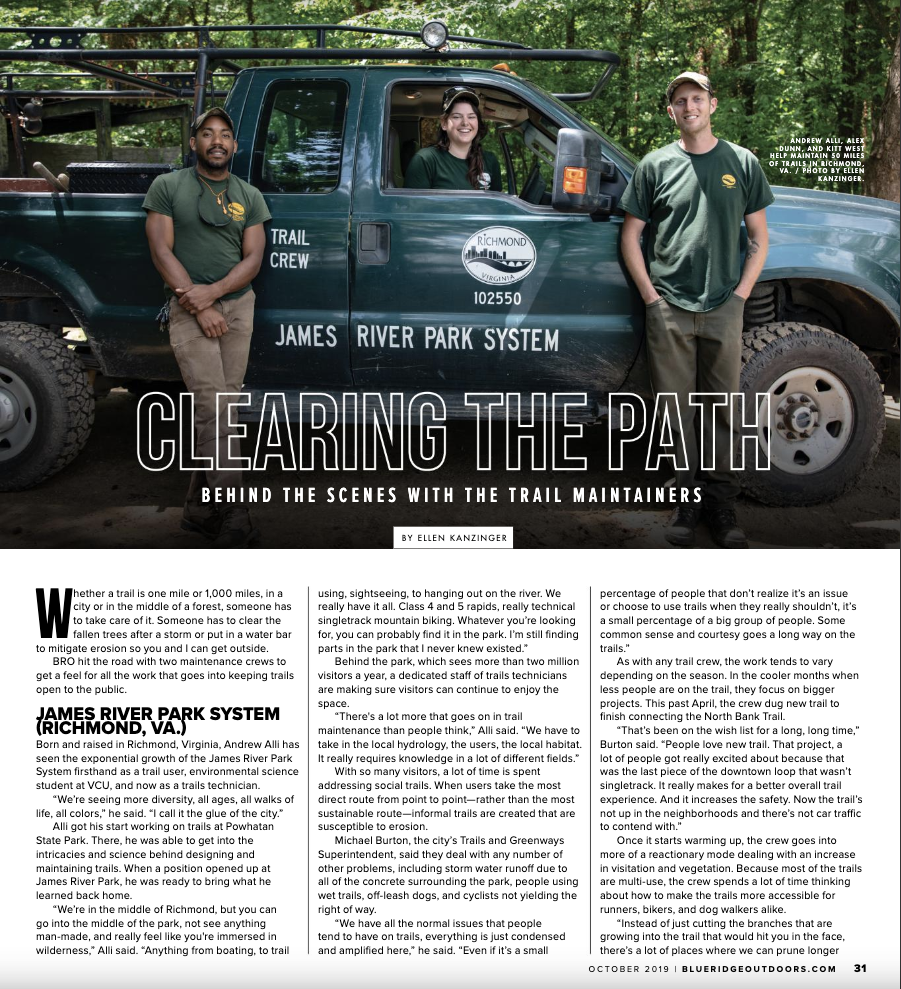

Born and raised in Richmond, Virginia, Andrew Alli has seen the exponential growth of the James River Park System firsthand as a trail user, environmental science student at VCU, and now as a trails technician.

“We’re seeing more diversity, all ages, all walks of life, all colors,” he said. “I call it the glue of the city.”

Alli got his start working on trails at Powhatan State Park. There, he was able to get into the intricacies and science behind designing and maintaining trails. When a position opened up at James River Park, he was ready to bring what he learned back home.

“We’re in the middle of Richmond, but you can go into the middle of the park, not see anything man-made, and really feel like you’re immersed in wilderness,” Alli said. “Anything from boating, to trail using, sightseeing, to hanging out on the river. We really have it all. Class 4 and 5 rapids, really technical singletrack mountain biking. Whatever you’re looking for, you can probably find it in the park. I’m still finding parts in the park that I never knew existed.”

Behind the park, which sees more than two million visitors a year, a dedicated staff of trails technicians are making sure visitors can continue to enjoy the space.

“There’s a lot more that goes on in trail maintenance than people think,” Alli said. “We have to take in the local hydrology, the users, the local habitat. It really requires knowledge in a lot of different fields.”

With so many visitors, a lot of time is spent addressing social trails. When users take the most direct route from point to point—rather than the most sustainable route—informal trails are created that are susceptible to erosion.

Michael Burton, the city’s Trails and Greenways Superintendent, said they deal with any number of other problems, including storm water runoff due to all of the concrete surrounding the park, people using wet trails, off-leash dogs, and cyclists not yielding the right of way.

“We have all the normal issues that people tend to have on trails, everything is just condensed and amplified here,” he said. “Even if it’s a small percentage of people that don’t realize it’s an issue or choose to use trails when they really shouldn’t, it’s a small percentage of a big group of people. Some common sense and courtesy goes a long way on the trails.”

As with any trail crew, the work tends to vary depending on the season. In the cooler months when less people are on the trail, they focus on bigger projects. This past April, the crew dug new trail to finish connecting the North Bank Trail.

“That’s been on the wish list for a long, long time,” Burton said. “People love new trail. That project, a lot of people got really excited about because that was the last piece of the downtown loop that wasn’t singletrack. It really makes for a better overall trail experience. And it increases the safety. Now the trail’s not up in the neighborhoods and there’s not car traffic to contend with.”

Once it starts warming up, the crew goes into more of a reactionary mode dealing with an increase in visitation and vegetation. Because most of the trails are multi-use, the crew spends a lot of time thinking about how to make the trails more accessible for runners, bikers, and dog walkers alike.

“Instead of just cutting the branches that are growing into the trail that would hit you in the face, there’s a lot of places where we can prune longer distance sightlines,” Burton said. “We’re always looking at places where we can prune both sides of the tree that’ll allow you to see around the corner better. We’re always looking for areas we can put in passing spots, places where we can create additional room in the trail tread to where people can get past each other easier.”

The fact that mountain bikers are still allowed on the trails is unique to the Richmond trails in comparison to other urban trail systems.

“Once they reach a certain amount of usage, mountain bikers wind up getting runoff from the trails because there’s too much potential for conflict,” Burton said. “A big part of what I view my job as is protecting mountain bikers’ access to these trails. The mountain biking community has been the driving force in Richmond for the construction of these trails. So, they’ve earned the right to use these trails.”

Meeting the City’s Needs

2019 has been a transition year for the trail crew. Whereas trail operations used to fall under the James River Park System, the city of Richmond decided to restructure and make Trails and Greenways its own division under Parks and Recreation.

Burton said the change was made so the department could direct more effort into other parks in the area beyond the James River.

“We’re expanding our reach,” he said. “We’re doing some maintenance and improvements to some trails that, in the past, have gotten a little less attention. James River Park gets the majority of the volume, usage, and it’s the trails that Richmond is known for. But there are a lot of other parks, like Pine Camp, Brian Park, Powhite Park, that we’re able to make improvements to trail systems.” The crew is responsible for 50 miles of trails and greenways in the city, 21 of which are in the James River Park.

Alex Dunn, one of the newest additions, has done trail work across the country. After doing a stint in AmeriCorps, she joined the National Park Service and worked on trail crews for Acadia, Yosemite, and Saguaro National Park.

Like Alli, Dunn was excited to return to her hometown while doing the work she loved.

“A lot of the work is very similar,” she said “It is keeping trails safe for users and mitigating erosion. Regionally, there are different climates and different terrains, but I would say the work is pretty similar. When I was in Arizona, I was actually mule-packing. We don’t do that here.”

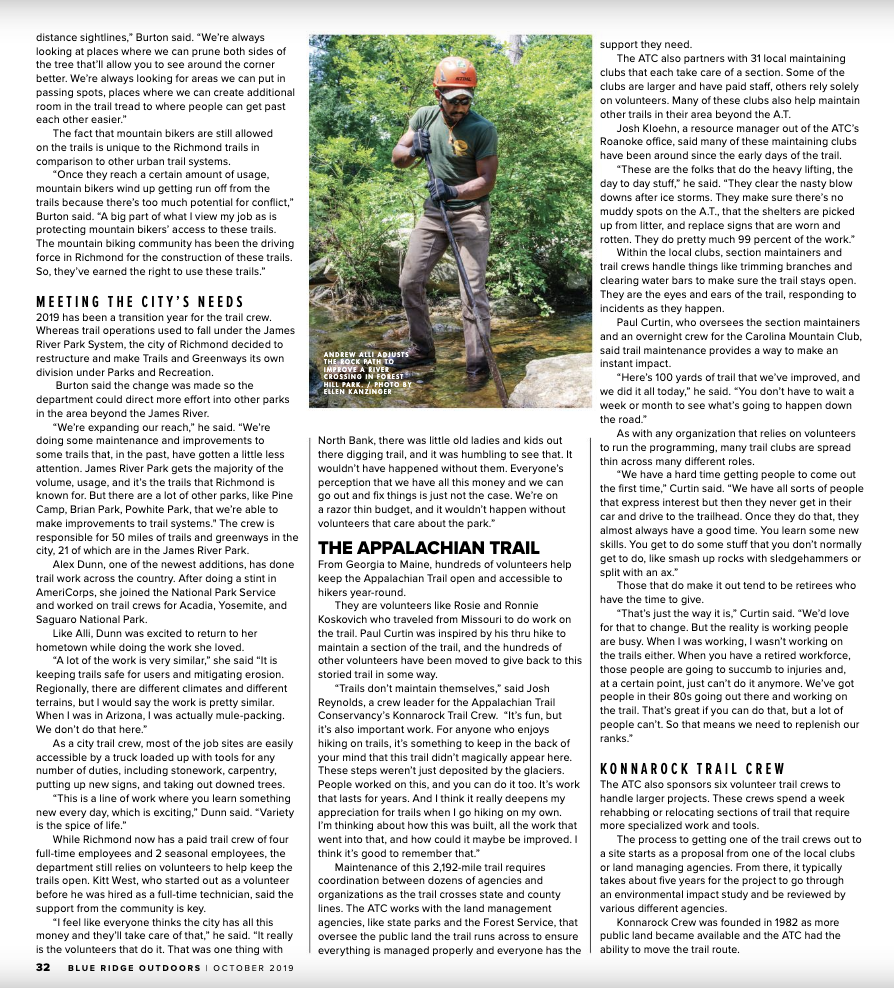

As a city trail crew, most of the job sites are easily accessible by a truck loaded up with tools for any number of duties, including stonework, carpentry, putting up new signs, and taking out downed trees.

“This is a line of work where you learn something new every day, which is exciting,” Dunn said. “Variety is the spice of life.”

While Richmond now has a paid trail crew of four full-time employees and 2 seasonal employees, the department still relies on volunteers to help keep the trails open. Kitt West, who started out as a volunteer before he was hired as a full-time technician, said the support from the community is key.

“I feel like everyone thinks the city has all this money and they’ll take care of that,” he said. “It really is the volunteers that do it. That was one thing with North Bank, there was little old ladies and kids out there digging trail, and it was humbling to see that. It wouldn’t have happened without them. Everyone’s perception that we have all this money and we can go out and fix things is just not the case. We’re on a razor-thin budget, and it wouldn’t happen without volunteers that care about the park.”

The Appalachian Trail

From Georgia to Maine, hundreds of volunteers help keep the Appalachian Trail open and accessible to hikers year-round.

They are volunteers like Rosie and Ronnie Koskovich who traveled from Missouri to do work on the trail. Paul Curtin was inspired by his thru hike to maintain a section of the trail, and the hundreds of other volunteers have been moved to give back to this storied trail in some way.

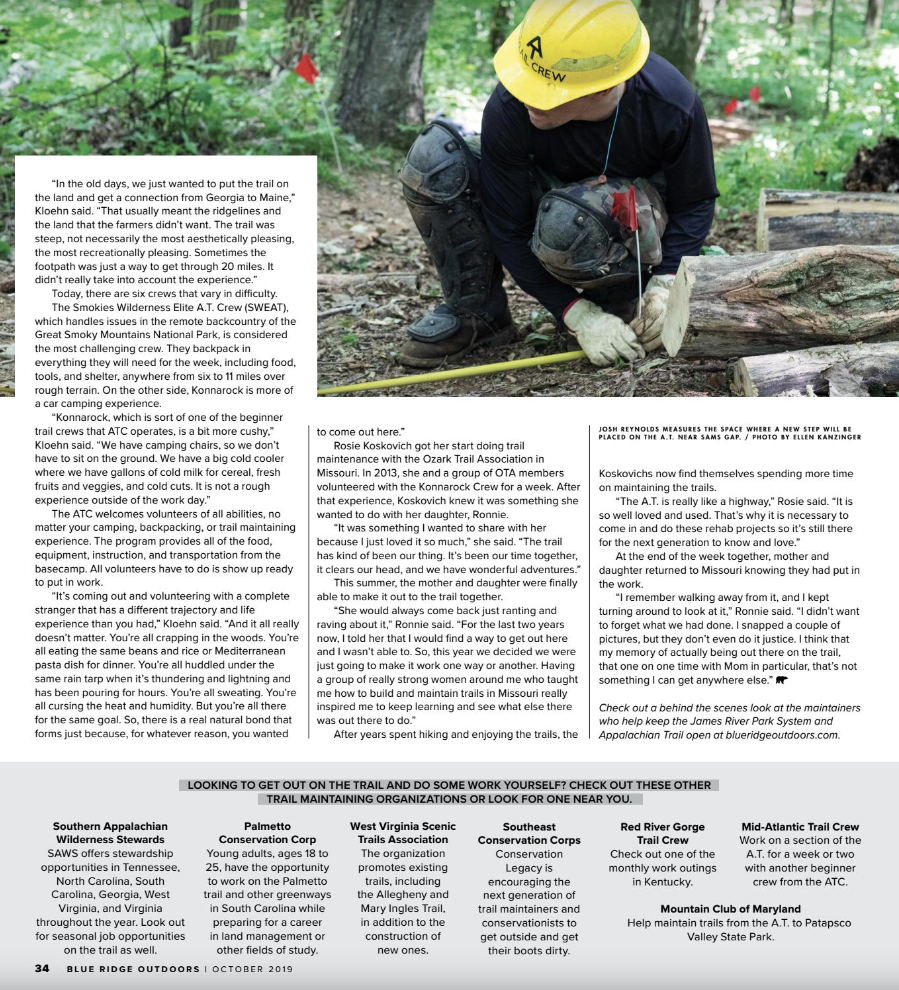

“Trails don’t maintain themselves,” said Josh Reynolds, a crew leader for the Appalachian Trail Conservancy’s Konnarock Trail Crew. “It’s fun, but it’s also important work. For anyone who enjoys hiking on trails, it’s something to keep in the back of your mind that this trail didn’t magically appear here. These steps weren’t just deposited by the glaciers. People worked on this, and you can do it too. It’s work that lasts for years. And I think it really deepens my appreciation for trails when I go hiking on my own. I’m thinking about how this was built, all the work that went into that, and how could it maybe be improved. I think it’s good to remember that.”

Maintenance of this 2,192-mile trail requires coordination between dozens of agencies and organizations as the trail crosses state and county lines. The ATC works with the land management agencies, like state parks and the Forest Service, that oversee the public land the trail runs across to ensure everything is managed properly and everyone has the support they need.

The ATC also partners with 31 local maintaining clubs that each take care of a section. Some of the clubs are larger and have paid staff, others rely solely on volunteers. Many of these clubs also help maintain other trails in their area beyond the A.T.

“Sometimes, being outside scares people. If I can make that experience easier for them because the trail is better, then that inspires me to keep doing it.”

Josh Kloehn, a resource manager out of the ATC’s Roanoke office, said many of these maintaining clubs have been around since the early days of the trail.

“These are the folks that do the heavy lifting, the day to day stuff,” he said. “They clear the nasty blow downs after ice storms. They make sure there’s no muddy spots on the A.T., that the shelters are picked up from litter, and replace signs that are worn and rotten. They do pretty much 99 percent of the work.”

Within the local clubs, section maintainers and trail crews handle things like trimming branches and clearing water bars to make sure the trail stays open. They are the eyes and ears of the trail, responding to incidents as they happen.

Paul Curtin, who oversees the section maintainers and an overnight crew for the Carolina Mountain Club, said trail maintenance provides a way to make an instant impact.

“Here’s 100 yards of trail that we’ve improved, and we did it all today,” he said. “You don’t have to wait a week or month to see what’s going to happen down the road.”

As with any organization that relies on volunteers to run the programming, many trail clubs are spread thin across many different roles.

“We have a hard time getting people to come out the first time,” Curtin said. “We have all sorts of people that express interest but then they never get in their car and drive to the trailhead. Once they do that, they almost always have a good time. You learn some new skills. You get to do some stuff that you don’t normally get to do, like smash up rocks with sledgehammers or split with an ax.”

Those that do make it out tend to be retirees who have the time to give.

“That’s just the way it is,” Curtin said. “We’d love for that to change. But the reality is working people are busy. When I was working, I wasn’t working on the trails either. When you have a retired workforce, those people are going to succumb to injuries and, at a certain point, just can’t do it anymore. We’ve got people in their 80s going out there and working on the trail. That’s great if you can do that, but a lot of people can’t. So that means we need to replenish our ranks.”

Konnarock Trail Crew

The ATC also sponsors six volunteer trail crews to handle larger projects. These crews spend a week rehabbing or relocating sections of trail that require more specialized work and tools.

The process to getting one of the trail crews out to a site starts as a proposal from one of the local clubs or land managing agencies. From there, it typically takes about five years for the project to go through an environmental impact study and be reviewed by various different agencies.

Konnarock Crew was founded in 1982 as more public land became available and the ATC had the ability to move the trail route.

“In the old days, we just wanted to put the trail on the land and get a connection from Georgia to Maine,” Kloehn said. “That usually meant the ridgelines and the land that the farmers didn’t want. The trail was steep, not necessarily the most aesthetically pleasing, the most recreationally pleasing. Sometimes the footpath was just a way to get through 20 miles. It didn’t really take into account the experience.”

Today, there are six crews that vary in difficulty.

“Be prepared to be dirty. Be prepared to have a lot of fun and meet great people.”

The Smokies Wilderness Elite A.T. Crew (SWEAT), which handles issues in the remote backcountry of the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, is considered the most challenging crew. They backpack in everything they will need for the week, including food, tools, and shelter, anywhere from six to 11 miles over rough terrain. On the other side, Konnarock is more of a car camping experience.

“Konnarock, which is sort of one of the beginner trail crews that ATC operates, is a bit more cushy,” Kloehn said. “We have camping chairs, so we don’t have to sit on the ground. We have a big cold cooler where we have gallons of cold milk for cereal, fresh fruits and veggies, and cold cuts. It is not a rough experience outside of the workday.”

The ATC welcomes volunteers of all abilities, no matter your camping, backpacking, or trail maintaining experience. The program provides all of the food, equipment, instruction, and transportation from the basecamp. All volunteers have to do is show up ready to put in work.

“It’s coming out and volunteering with a complete stranger that has a different trajectory and life experience than you had,” Kloehn said. “And it all really doesn’t matter. You’re all crapping in the woods. You’re all eating the same beans and rice or Mediterranean pasta dish for dinner. You’re all huddled under the same rain tarp when it’s thundering and lightning and has been pouring for hours. You’re all sweating. You’re all cursing the heat and humidity. But you’re all there for the same goal. So, there is a real natural bond that forms just because, for whatever reason, you wanted to come out here.”

Rosie Koskovich got her start doing trail maintenance with the Ozark Trail Association in Missouri. In 2013, she and a group of OTA members volunteered with the Konnarock Crew for a week. After that experience, Koskovich knew it was something she wanted to do with her daughter, Ronnie.

“It was something I wanted to share with her because I just loved it so much,” she said. “The trail has kind of been our thing. It’s been our time together, it clears our head, and we have wonderful adventures.”

This summer, the mother and daughter were finally able to make it out to the trail together.

“She would always come back just ranting and raving about it,” Ronnie said. “For the last two years now, I told her that I would find a way to get out here and I wasn’t able to. So, this year we decided we were just going to make it work one way or another. Having a group of really strong women around me who taught me how to build and maintain trails in Missouri really inspired me to keep learning and see what else there was out there to do.”

After years spent hiking and enjoying the trails, the Koskovichs now find themselves spending more time on maintaining the trails.

“The A.T. is really like a highway,” Rosie said. “It is so well-loved and used. That’s why it is necessary to come in and do these rehab projects so it’s still there for the next generation to know and love.”

At the end of the week together, mother and daughter returned to Missouri knowing they had put in the work.

“I remember walking away from it, and I kept turning around to look at it,” Ronnie said. “I didn’t want to forget what we had done. I snapped a couple of pictures, but they don’t even do it justice. I think that my memory of actually being out there on the trail, that one on one time with Mom in particular, that’s not something I can get anywhere else.”

This article originally appeared in Blue Ridge Outdoors Magazine’s October 2019 issue.