A Path Forward

From Industry to Recreation: Turning Rails into Trails

Born and raised in Southwest Virginia, Eva Beaule’s family depended on tobacco agriculture for income. Washington County was one of the country’s largest producers of burley tobacco leaves and, at that time, a rail line linking Mendota and Bristol, Va., carried products in and out of the county.

“I remember very well when the train was there, and the community was built somewhat around that train and the commerce it brought in,” Beaule said. “I am a complete advocate for a tobacco free lifestyle. But, at the same time, I acknowledge what it meant to my community and my family.”

Beaule eventually moved to another part of the state and, like many smaller towns, the train and tobacco left the area, taking a large part of the local economy with it.

Now Beaule has returned to her hometown and is part of a growing effort to convert that abandoned Virginia & Southwestern Railroad line into the Mendota Trail, a 12.5 miles multi-use recreational trail.

“It’s fun to meet people on the trail and it brings people together,” she said. “But in the case of the Mendota, I also see it as a potential economic catalyst for what is fast becoming a lost community.”

The rail-trails movement began in the Midwest as railroad companies consolidated and closed irrelevant lines. Communities were left with abandoned rails running through town.

Construction of the first rail-trail began in 1965 on the 32.5-mile Elroy-Sparta State Trail in Wisconsin. According to the Rails to Trails Conservancy, there are now more than 2,000 rails-trails around the country, covering almost 23,700 miles.

The Virginia Creeper Trail, a popular trail located about 45 minutes from Mendota, sees upwards of 250,000 visitors every year.

An economic impact study done by Key-Log Economics estimates that 50,000 visitors to the Mendota Trail would add $655,700 to the local economy and create 11 jobs.

Bristol already has the amenities like hotels and breweries in place and draws crowds for various events like the Rhythm and Roots Reunion and race weekend. Volunteers hope the trail will help draw visitors year-round.

Beaule owns Adventure Mendota, a kayaking outfitter operating on the North Fork of the Holston River. After a day on the water, Beaule said visitors often ask what other outdoor recreation opportunities are available in the area.

She tells them to be patient. Something is in the works.

“There’s no wavering in my thought process,” she said. “I’m convinced that it will be the best thing in my lifetime that I will see to be an economic catalyst. People see that trails are safe, they’re economic drivers, and they bring people to the area who are good stewards of the land.”

This is not the first time the citizens of Washington County have tried to convert the abandoned line into a new source of revenue. Several attempts to turn the rail line into an excursion train or a recreational trail failed for various reasons.

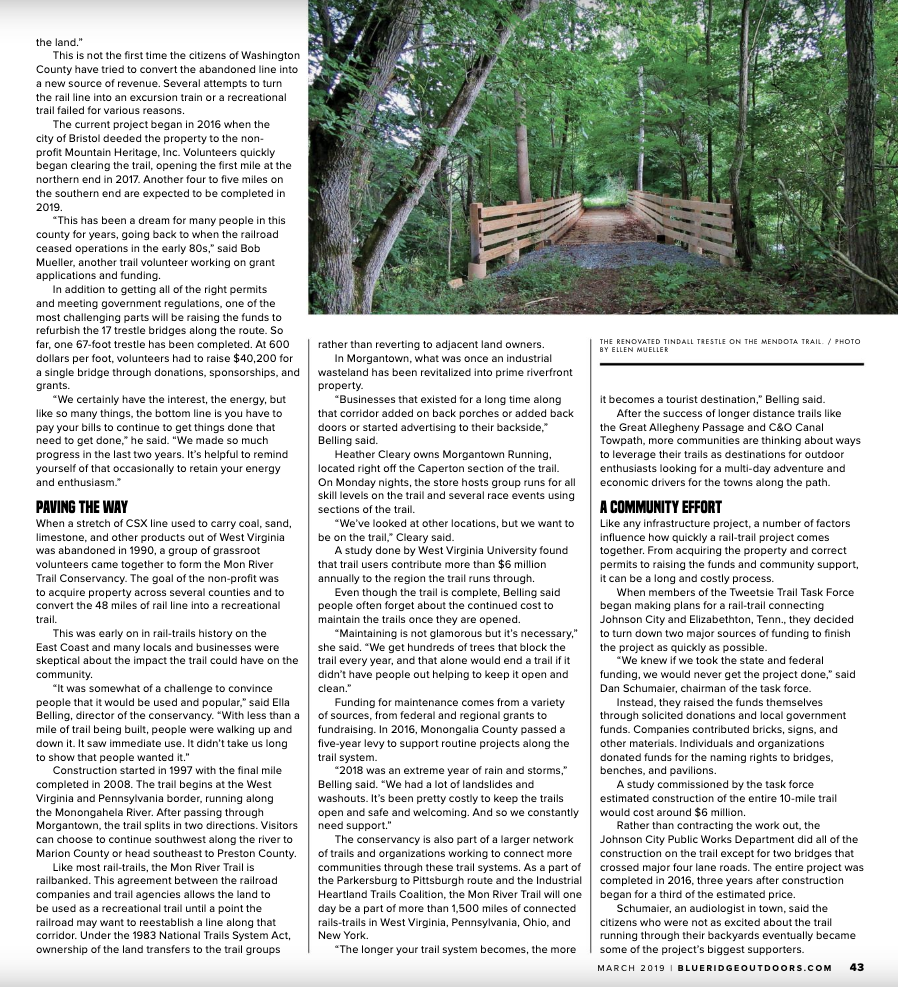

The current project began in 2016 when the city of Bristol deeded the property to the non-profit Mountain Heritage, Inc. Volunteers quickly began clearing the trail, opening the first mile at the northern end in 2017. Another four to five miles on the southern end are expected to be completed in 2019.

“This has been a dream for many people in this county for years, going back to when the railroad ceased operations in the early 80s,” said Bob Mueller, another trail volunteer working on grant applications and funding.

In addition to getting all of the right permits and meeting government regulations, one of the most challenging parts will be raising the funds to refurbish the 17 trestle bridges along the route. So far, one 67-foot trestle has been completed. At 600 dollars per foot, volunteers had to raise $40,200 for a single bridge through donations, sponsorships, and grants.

“We certainly have the interest, the energy, but like so many things, the bottom line is you have to pay your bills to continue to get things done that need to get done,” he said. “We made so much progress in the last two years. It’s helpful to remind yourself of that occasionally to retain your energy and enthusiasm.”

Paving the Way

When a stretch of CSX line used to carry coal, sand, limestone, and other products out of West Virginia was abandoned in 1990, a group of grassroot volunteers came together to form the Mon River Trail Conservancy. The goal of the non-profit was to acquire property across several counties and to convert the 48 miles of rail line into a recreational trail.

This was early on in rail-trails history on the East Coast and many locals and businesses were skeptical about the impact the trail could have on the community.

“It was somewhat of a challenge to convince people that it would be used and popular,” said Ella Belling, director of the conservancy. “With less than a mile of trail being built, people were walking up and down it. It saw immediate use. It didn’t take us long to show that people wanted it.”

Construction started in 1997 with the final mile completed in 2008. The trail begins at the West Virginia and Pennsylvania border, running along the Monongahela River. After passing through Morgantown, the trail splits in two directions. Visitors can choose to continue southwest along the river to Marion County or head southeast to Preston County.

Like most rail-trails, the Mon River Trail is railbanked. This agreement between the railroad companies and trail agencies allows the land to be used as a recreational trail until a point the railroad may want to reestablish a line along that corridor. Under the 1983 National Trails System Act, ownership of the land transfers to the trail groups rather than reverting to adjacent land owners.

In Morgantown, what was once an industrial wasteland has been revitalized into prime riverfront property.

“Businesses that existed for a long time along that corridor added on back porches or added back doors or started advertising to their backside,” Belling said.

Heather Cleary owns Morgantown Running, located right off the Caperton section of the trail. On Monday nights, the store hosts group runs for all skill levels on the trail and several race events using sections of the trail.

“We’ve looked at other locations, but we want to be on the trail,” Cleary said.

A study done by West Virginia University found that trail users contribute more than $6 million annually to the region the trail runs through.

Even though the trail is complete, Belling said people often forget about the continued cost to maintain the trails once they are opened.

“Maintaining is not glamorous but it’s necessary,” she said. “We get hundreds of trees that block the trail every year, and that alone would end a trail if it didn’t have people out helping to keep it open and clean.”

Funding for maintenance comes from a variety of sources, from federal and regional grants to fundraising. In 2016, Monongalia County passed a five-year levy to support routine projects along the trail system.

“2018 was an extreme year of rain and storms,” Belling said. “We had a lot of landslides and washouts. It’s been pretty costly to keep the trails open and safe and welcoming. And so we constantly need support.”

The conservancy is also part of a larger network of trails and organizations working to connect more communities through these trail systems. As a part of the Parkersburg to Pittsburgh route and the Industrial Heartland Trails Coalition, the Mon River Trail will one day be a part of more than 1,500 miles of connected rails-trails in West Virginia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, and New York.

“The longer your trail system becomes, the more it becomes a tourist destination,” Belling said.

After the success of longer distance trails like the Great Allegheny Passage and C&O Canal Towpath, more communities are thinking about ways to leverage their trails as destinations for outdoor enthusiasts looking for a multi-day adventure and economic drivers for the towns along the path.

A Community Effort

Like any infrastructure project, a number of factors influence how quickly a rail-trail project comes together. From acquiring the property and correct permits to raising the funds and community support, it can be a long and costly process.

When members of the Tweetsie Trail Task Force began making plans for a rail-trail connecting Johnson City and Elizabethton, Tenn., they decided to turn down two major sources of funding to finish the project as quickly as possible.

“We knew if we took the state and federal funding, we would never get the project done,” said Dan Schumaier, chairman of the task force.

Instead, they raised the funds themselves through solicited donations and local government funds. Companies contributed bricks, signs, and other materials. Individuals and organizations donated funds for the naming rights to bridges, benches, and pavilions.

A study commissioned by the task force estimated construction of the entire 10-mile trail would cost around $6 million.

Rather than contracting the work out, the Johnson City Public Works Department did all of the construction on the trail except for two bridges that crossed major four lane roads. The entire project was completed in 2016, three years after construction began for a third of the estimated price.

Schumaier, an audiologist in town, said the citizens who were not as excited about the trail running through their backyards eventually became some of the project’s biggest supporters.

“A lot of people didn’t think it was going to happen,” he said. “Once it started to become a reality, the community really jumped behind this project. When communities get together, the potential they can unleash is really amazing. That’s what we did.”

The popularity of the trail was almost instantaneous. Phil Pindzola, the director of public works, said the trail averages around 1,000 visitors a day with an event almost every weekend. Both downtowns have seen a revitalization as the cities try to attract new businesses and people to the area.

A Trek Bicycle store opened in Johnson City due in part to the construction of the trail. Pindzola said sales are up more than 100 percent at the Trek store for the third year in a row. Local Motion, a full-service bike shop, opened at the trailhead on the Johnson City end in 2017. The shop offers bike rentals and repairs, as well as ice cream after a long ride.

“We’re trying to figure out how to grow,” Pindzola said. “If you enhance the quality of life in the community, then people may be more likely to want to be a part of the community. When we built the Tweetsie Trail, what was immediately recognized was the value that trail had towards the quality of life.”

After the success of the Tweetsie, Johnson City is looking at creating a major trail system through the city, connecting the Tweetsie to other smaller trails and public parks. Tannery Knob, a mountain bike park, is set to open soon.

Connecting the East Coast

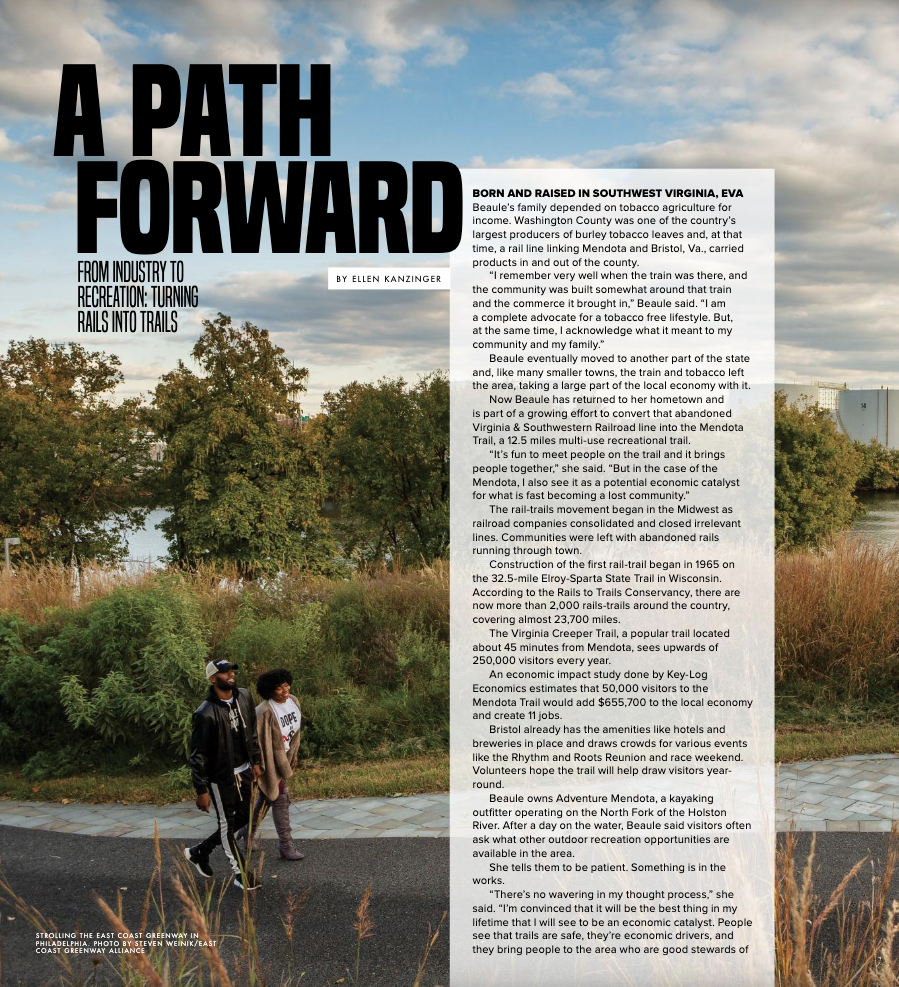

It’s an ambitious project to connect the entire East Coast, from Key West, Fla. to the Maine-Canada border, on one continuous greenway.

Dennis Markatos-Soriano, the executive director of the East Coast Greenway Alliance, said the goal is to create a place “where people can enjoy low cost transportation, lower costs in health care, and just have fun outside.”

The project will give communities access to local trails as well as the opportunity to take on bigger adventures, traveling to far-away cities through human powered transportation.

A study done by Rutgers Professor John Pucher found that cities like Charlotte, Atlanta, and Richmond have seen the number of bicycle commuters more than double from 2000 to 2015.

Markatos-Soriano said he feels a sense of urgency to complete the trail, setting what he calls an “audacious goal” for 2030.

“From the obesity epidemic to climate change, it’s really important for us to have tangible projects and infrastructure that help people live the healthy and sustainable lifestyle that they want to,” he said.

Plans for the greenway have been underway since the early 90s when leaders of local greenway projects in major cities like Boston, New York, and D.C. came together to develop a connecting trail similar to the Appalachian Trail. Cities along the A.T. have experienced an economic revitalization as hikers pass through, stopping to refuel and enjoy a warm meal.

The greenway could have a similar affect, although it is designed to be an urban trail connecting more than 450 communities across 3,000-plus miles.

In some states, especially in the north, miles and miles of greenways and trails have already been built. Other states have some catching up to do.

By the end of 2018, more than 1,000 miles of trail built in patches up and down the East Coast are on protected greenways. Many of those miles come from abandoned rail lines turned into trails. The remaining two thirds of the trail are currently on right of ways on the side of roads.

Although it is possible to bike or walk the entire East Coast Greenway route as it is right now, the goal is to eventually move the entire trail off road.

“When you’re on the greenway, you’re not separated from other people by your windshield,” Markatos-Soriano said. “You’re encountering people and you’re developing relationships with people.”

The most challenging part for the alliance and supporters of the greenway will be to keep the enthusiasm going as funds are continuously needed to acquire land and connect existing trails. As the greenway becomes more well-known and communities see the benefits this kind of trail network could bring, more people will be able to take advantage of the project.

The Triangle area of North Carolina is home to the longest stretch of completed greenway with almost 70 miles of linked trails. A study of the impacts of greenways in the Triangle by Alta Planning + Design estimates that the region gains more that $90 million in health, environmental, transportation, property, and economic benefits from the trails every year.

Although the majority of the East Coast Greenway is still on the road, almost 30 bikers and hikers have completed the entire route.

Lisa Watts, the communications manager for the alliance, took two months off work in the summer of 2018 to bike the entire route with a friend.

“I grew up in Atlanta, Baltimore, and Boston and always had this kind of notion of riding my bike at some point, connecting all of those dots,” she said. “It’s been on my bucket list since I was 25.”

It took the pair 57 days to ride up the entire coast, averaging between 60 to 70 miles a day.

Every day was an adventure and the realization of a lifelong dream as the friends navigated the trail.

“When you do end up riding a couple of miles on a greenway, it’s such a treat,” Watts said. “You’ve been managing traffic and noise on a busy road. Then you turn and you can ride side by side, talk to each other, and not constantly be worried about what’s coming up behind you.”

For Watts, the south-to-north cross-country trip appealed to her more than an East-to-West Coast trip because there would be shorter stretches riding through unpopulated areas, and they would not have to cross the Rocky Mountains.

Along the way, they stayed with family and friends. Strangers, many of whom had never heard of the project, provided bottles of water on hot summer days and showed an interest in one day undertaking a similar journey of their own.

“People are so kind,” Watts said. “A woman offered us her house in Georgia when we were planning to go to a motel. A host helped me change my tire. People gave directions and they’re always interested in what you’re doing. It just reinforces what we’re doing and why we’re doing it.”

This article originally appeared in Blue Ridge Outdoors Magazine’s March 2019 issue.